The Long Maji Maji Rebellion

In 2004, researchers in the dense forests of Walikale territory in North Kivu, eastern Congo, encountered fighters from a militia calling itself Mai-Mai Simba. These armed men claimed their movement traced its lineage directly to the Simba rebellion of 1964, which itself drew on practices from the Maji Maji uprising against German colonialism in 1905. Indeed, the term “Mai-Mai” (or “Mayi-Mayi”) itself reflects the Congolese pronunciation and spelling of the Swahili phrase “Maji-Maji,” maji meaning “water.”

Being familiar with the longue durée history of the interlacustrine region—the world surrounding the great lakes of East and Central Africa, connecting Burundi, Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia—I want to argue that this a matter of profound significance. What the Mai-Mai practiced, protective medicine combined with moral discipline to organize collective defense, had persisted across generations, a theme whose variations adapted to new enemies.

This lecture traces that theme across 120 years. Its focus is the greater interlacustrine Bantu and Swahili world. What I am calling the Long Maji Maji is a transversal regional formation, a grammar of resistance that predates colonial rule, that has outlasted every regime that attempts to suppress it, and that activates precisely when those regimes fail to protect the populations they claim to govern. Three regimes of modernizing power—German colonialism, African nationalism, and neocolonial clientism—have attempted its elimination through military force and cultural suppression. All have failed. Today, as extra-colonial humanitarian peacekeeping missions and development programs frame Mai-Mai groups as disorder requiring management, a fourth regime reproduces the same pattern: suppression, apparent defeat, transformation, return.

The question driving this analysis is not whether Mai-Mai violence is justifiable. The historical record documents brutalities that cannot be excused within any framework. That remains true even if the regimes that have sought to suppress the Mai-Mai have themselves committed murders—by commission and by omission—on a far greater scale. The issue is not moral equivalence. It is persistence: why have four successive regimes of modernizing power, across more than a century, failed to eliminate a formation they cannot recognize as a political response to their own extreme violence and structural failures?

Each regime that has confronted the Long Maji Maji—colonial, anti-colonial nationalist, neocolonial, and extra-colonial humanitarian—has seen only primitive superstition, an obstacle to modernization, or an armed problem requiring pacification. This presistent misrecognition has helped ensure its repeated re-emergence. But to understand what is at stake, we must first understand what the formation emerges in response to.

The Warren: Three Scrambles for Africa

The history of Empire’s engagement with the African continent falls into three overlapping phases—what I call the three Scrambles—each building on the infrastructure of the last, each producing the conditions that activate the next wave of resistance.

The First Scramble for Africa, “The Slave Trade,” was the proto-colonial competition to convert Africa into what Karl Marx called “a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins”: to kidnap and export enslaved Africans to the New World.

Consider what that phrase actually names. Not a metaphor. A practice. To hunt commercially is to reorganize a territory around the act of capture—to render a living world into a supply zone, its peoples into prey, its landscapes into corridors of extraction, its political orders into mechanisms of delivery. And what was being extracted? Achille Mbembe gives us the term: ambulant suns. Living energy. Human flesh as fossil fuel. The enslaved were not merely laborers shipped to the New World; they were the energy source of an entire industrial order—bodies burned through like coal to power the terraforming of Turtle Island, Abya Yala, and Pindorama into Neo-Europes; the plantations that enriched them; the factories that processed their yields; the financial instruments that leveraged their output; the empires that named themselves modernity. Africa was not adjacent to the story of extraction. It was the original energy field.

What does it mean to consume flesh as fossil fuel? In the deadliest plantation regimes of the New World,the average remaining lifespan of a trafficked African was reckoned at seven years. Seven years of labor extracted, then death, then replacement—new bodies purchased to fill the places of the spent. Not maintained. Not sustained. Burned through and replenished from the supply zone, exactly as a furnace burns through coal and demands more from the mine. For roughly the first two of its four centuries, the plantation regime did not depend on the reproduction of its labor force. It depended on the continuous extraction of new fuel from Africa. This is what made the warren necessary: not a one-time seizure but a perpetual supply operation, the continent reorganized as an inexhaustible energy field feeding an insatiable industrial engine.

According to the more maximalist UNESCO estimates, between twenty-five and thirty million of these ambulant suns were kidnapped, deported, and subjected to slavery and social death across four centuries. When you account for those killed during and in long the destructive wake of slave raids, in holding camps, on death marches to coastal ports, and during the Middle Passage, the total number of lives extracted from the continent may be one hundred million.

One hundred million. The number is so large it becomes abstract, which is precisely what Empire wants. Abstract numbers do not haunt. They can be filed, cited, debated. They become content for history courses and museum exhibits.

And this is to say nothing of those who remained on the continent, surviving and suffering half-lives in the wake of those apocalyptic disappearances and mass premature deaths. These were not merely the destruction of peoples. They were the rending of social fabric: trade routes severed, governance systems shattered, architectures of knowledge and relation razed. Whole civilizations did not vanish; they were hollowed out, left standing but emptied of the kinship, continuity, and collective capacity that had made them what they were.

And even this is not yet the full picture. For Africa to function as a warren, the warren had to be built. Consider what must be done to a region before its oil becomes extractable—the roads cut, the rivers poisoned, the communities displaced, the governance captured, the land itself remade into a delivery system for what lies beneath it. The slave trade required its own equivalent: a vast, destructive infrastructure laid down across the continent and maintained across centuries. Fortified trading posts along the coast. Inland networks of coerced intermediaries. The systematic destabilization of societies that resisted conscription into the supply chain. The militarization of those that cooperated. The deliberate production of chaos in regions targeted for raiding, so that war itself became the engine of capture. This was the drilling apparatus. Africa was the well.

This infrastructure was not incidental to the transatlantic slave trade. It was its other half—the half that remains most invisible, because it was designed to look like the natural condition of the continent rather than the manufactured ruin it was. The New World received the ambulant suns and burned them. Africa absorbed the apparatus of their extraction.

The Second Scramble for Africa, “The Land Grabs,” began in the wake of the “non-event of emancipation” and the closing of the frontiers of the New World. It marked the full-blown colonial campaign to conquer, exploit, and dominate the African continent through extreme violence.

The speed of this conquest is often treated as evidence of African weakness. But it was actually evidence of the First Scramble’s success. Four centuries of the warren had already done the work: governance systems shattered, trade networks redirected toward the coast, societies militarized against one another, populations depleted by a hundred million lives extracted or destroyed. The drilling apparatus built to feed the New World’s furnaces had left the continent structurally hollowed. Europeans did not conquer a healthy body but a patient they had spent centuries bleeding.

The intermediaries the First Scramble had empowered—the local rulers coerced or co-opted into supplying the trade—were now overthrown by the same Europeans who had empowered and enriched them. Having served their purpose as franchise managers of the warren, they were discarded. Europeans declared themselves the continent’s new “enlightened” governors.

Despite claims of having abolished slavery, they reconstituted its horrors in the interior of Africa. The Congo Free State became the most infamous example: a vast plantation-state where forced labor and terror killed an estimated ten million Congolese people in less than twenty-five years. Hands severed to meet rubber quotas. Villages burned. Children held hostage. Death by work and death by punishment and death by starvation—dispersed across a system so diffuse that its organizers could claim plausible deniability.

Ten million in the Congo alone. And the Congo was not unique. Across the continent, similar regimes extracted labor and life. The dead accumulated.

The political economist Issa Shivji describes the economy these regimes installed as “typically disarticulated, almost tailor-made, for exploitation by colonial capital, linked to the metropolitan trade and capital circuits.” Extractive industries predominated. Plantation agriculture existed alongside subsistence peasant cultivation, yes, but both the plantation and the subsistence plot concentrated on one or two crops for export according to the needs of the metropolitan economy. Entrepreneurship and skilled labor were deliberately suppressed. The urban and the rural became “literally two countries within one: one was alien, modern, a metropolitan transplant barred to the native—while the other was stagnant and frozen in so-called tradition or custom. Neither the modern nor the traditional were organically so. Both were colonial constructs.” This was not dysfunction. It was the economic logic of the Second Scramble: production organized to answer the accumulation needs of the center, not the survival needs of the periphery.

The Third Scramble for Africa, “The Debt Trap & Resource Curse,” is the ongoing neo-colonial and extra-colonial campaign to underdevelop and overburden postcolonial African states. Through extractive mechanisms such as debt repayments, natural resource exploitation, skilled labor migration, and political subservience to global economic blocs, neo-colonial powers maintain the continent’s subjugation.

Again, the continuity matters. The First Scramble hollowed the continent to fuel Empire. The Second walked into the hollowed body and installed direct rule. The Third inherits everything the first two built and broke: borders drawn to divide ethnic communities and fuel hostilities, economies structured around single export commodities chosen by colonial administrators, education systems designed to produce clerks and intermediaries rather than sovereign thinkers, governance institutions modeled on the colonial state and handed over at independence with the instructions still written in the colonizer’s language. What the world calls African dysfunction—the coups, the corruption, the debt, the brain drain, the collapsing infrastructure—is not a failure to develop. It is the warren still functioning. The drilling apparatus was never properly dismantled. It was inherited: the corrupt government administrators of the postcolonial territorial nation are the direct descendants of the corrupt European administrators of the colony.

The Third Scramble recalls the dynamics of the First. Instead of imposing direct rule, neo-colonial and extra-colonial enterprises bribe, corrupt, and terrorize postcolonial elites into sabotaging their nations’ futures. These elites—warlords or technocrats depending on the costume—function as agents of systemic underdevelopment, reminiscent of early modern African rulers coerced into selling their most vulnerable subjects and neighbors into chattel slavery. The mechanism is uncannily similar: identify local actors, bind them to external interests, let them administer the extraction so the extractors can claim clean hands.

Shivji articulates the mechanics precisely. The concept he develops—disarticulated accumulation—names the structural logic of the Third Scramble. In a disarticulated economy, “what is produced is not consumed and what is consumed is not produced.” Africa exports its coffee, cocoa, cotton, gold, diamonds, copper; very few of these products have internal markets. Meanwhile, imports are consumer, intermediate, and capital goods catering to narrow urban and elite consumption patterns. The needs of the large majority—food above all—are met by subsistence production or food aid. There are competing demands on peasant labor between cash crops for export and food crops for survival, and it is always food production that gives way. The surplus generated in agriculture is not accumulated within agriculture to propel its development. It is extracted upward through compradorial intermediaries and outward to the imperial cores, “accumulated as merchant capital to reproduce the extraverted economy.”

The numbers confirm the structure. According to UNCTAD, between 1970 and 1997, cumulative terms-of-trade losses for non-oil exporting countries in sub-Saharan Africa amounted to 119 percent of the region’s GDP. Had these losses not occurred, per capita income would have been fifty percent higher. Between 1982 and 1991, sub-Saharan Africa paid one billion dollars every month in debt service; by the end of the decade, its debt stock had more than doubled. Africa received $540 billion in loans between 1970 and 2002 and paid back $550 billion. Yet in 2002 it still owed $295 billion—because of imposed arrears, penalties, and interest. The debt runs the wrong direction. Africa does not owe. Africa is owed.

But the debts that are enforced are the debts to Empire. Structural adjustment programs. IMF conditionalities. Austerity regimes that strip public services while ensuring creditors are paid. These debts were designed to be unpayable, ensuring permanent dependency, keeping postcolonial states bound to the imperial order that claimed to have liberated them. Decolonization was not liberation. It was the transfer of the administration and operating costs of the warren to its inmates.

Drawing on Rosa Luxemburg and David Harvey, Shivji insists that primitive accumulation is not merely historical—it continues contemporaneously with the development of capitalism, specifically in the periphery. Luxemburg identified what she called the “dual character” of capital accumulation: one aspect concerns the commodity market and the factory, where “peace, property and equality prevail” in form; “the other aspect of the accumulation of capital concerns the relations between capitalism and the non-capitalist modes of production which start making their appearance on the international stage. Its predominant methods are colonial policy, an international loan system—a policy of spheres of interest—and war. Force, fraud, oppression, looting are openly displayed without any attempt at concealment.” Both aspects operate simultaneously, but in Africa the second dominates. The disarticulated character of peripheral accumulation means that “the destruction of accumulation by dispossession is imposed on African societies without having enjoyed the historical fruits created by the development of accumulation by expanded reproduction.” Empire plunders without pioneering. The periphery absorbs the violence of capitalist expansion without receiving any of its developmental benefits.

And the dead continue to accumulate. The children who die of preventable diseases because health systems have been gutted to meet debt obligations. The workers who die in mines extracting minerals for the global market. The migrants who die trying to reach shores that exploit their labor while denying their humanity.

This is what the Long Maji Maji resists. Not a single regime but an apparatus that reconfigures across centuries—an apparatus whose economic logic, as Shivji demonstrates, structurally ensures that the periphery generates surplus it can never accumulate, serves needs it can never meet, and depends on institutions that can never protect it. The Long Maji Maji formation resists through means that every version of that apparatus has declared illegitimate—not because those means are ineffective, but because recognizing their legitimacy would undermine the foundational claim that sovereignty must flow through centralized institutions the apparatus controls.

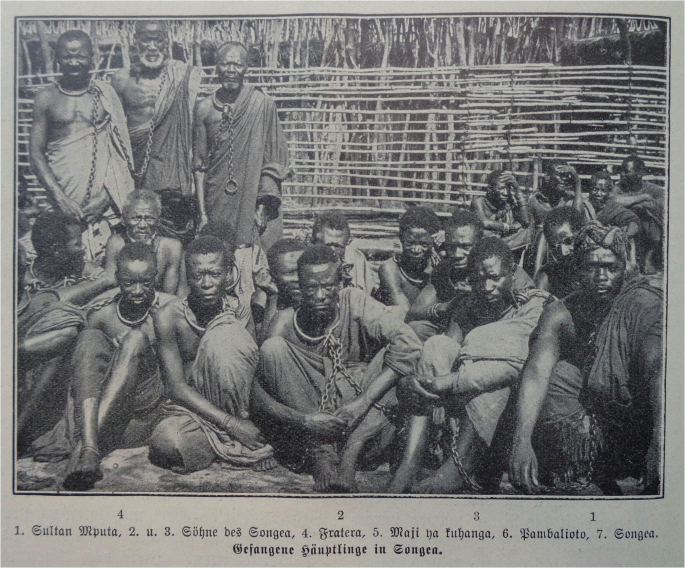

Maji Maji warriors before hanging in February 1906

The Long Maji Maji

The argument I want to make has six movements. Each traces the same formation—protective medicine combined with moral discipline, organizing collective defense through cosmological authorization rather than bureaucratic command—as it encounters a different regime of power, is suppressed, transforms, and returns.

1. The Regional Grammar

The practice of ritually treated water conferring protection on warriors existed across the interlacustrine world long before Maji Maji. Among the Lugbara between present-day Uganda and Congo, the Yakan cult centered on drinking water believed to confer invulnerability; neighboring Dinka and Mundu populations already employed such water against Arab slave raiders. The practice spread during the crises of the 1890s—epidemics, famine, the upheaval of the Mahdi revolt—and those who provided access to the water parlayed it into ritual authority. When the British suppressed Yakan militarily in 1919, the movement survived by contracting into a healing practice. The pattern was already established by then: crisis activates the grammar, suppression drives it underground, it persists in modified form, available for reactivation when the next crisis demands it. These practices were neither isolated to one ethnic group nor invented anew each time. They constituted a shared template for converting crisis into collective capacity when other sources of protection failed.

2. Maji Maji, 1905–1907

The uprising in German East Africa drew on this regional grammar while becoming its most famous instance. The context was the Second Scramble at its most brutal: German authorities attempting to refashion territories into cotton zones through forced labor modeled on neoslavery/sharecropping American South. A healer named Kinjikitile Ngwale, claiming possession by the spirit Hongo, began distributing maji—water treated with medicinal herbs said to neutralize ammunition. But the medicine came with strict requirements: sexual abstinence preventing the use of rape as weapon of war, food restrictions, behavioral discipline. These prohibitions created boundaries marking who belonged to the protected community. The practice addressed two problems simultaneously: the lack of unity among different populations, and the massive military disadvantage. Ritual achieved what political organization alone could not.

The Germans hanged Kinjikitile, but the practice had already proliferated through dispersed specialists called hongo who prepared maji across multiple ethnic groups. Scorched earth tactics eventually crushed the rebellion—burning villages, destroying crops, producing famine that killed as many as 300,000 people. But the constellation of practices Kinjikitile activated had proven its capacity: disparate marginalized populations converted into organized fighting force through cosmological alignment rather than bureaucratic control, through dispersed ritual networks rather than centralized command. The Germans won militarily but encountered something they could not fully suppress. After the defeat, the symbolic repertoire was taken up by prophetic figures leading purification movements—maintaining the grammar while redirecting it from anti-colonial warfare to internal transformation. The practice-knowledge survived in communities across the region, available for transmission when crisis would demand it again.

3. Nationalist Appropriation in Tanzania

When Tanzania achieved independence in 1961, Nyerere encountered Maji Maji as powerful but dangerous inheritance. The rebellion offered exactly the narrative nationalist historiography required: unified resistance by diverse peoples against foreign oppression. But its actual character—dispersed ritual networks, cosmological authorization exceeding political ideology, legitimacy derived from demonstrated capacity rather than institutional frameworks—threatened the centralized state Nyerere was building.

Shivji, who was at the University of Dar es Salaam during the debates that shaped Tanzania’s post-independence intellectual culture, describes the structural trap Nyerere faced. The colonial economy was “anything but national.” In the scramble for Africa, colonial powers had “divided the continent into mini-countries where boundaries cut through cultural, ethnic, and economic affinities.” Imperial policy left behind “extremely uneven development both within and between countries.” And the social class that inherited power at independence was, in Frantz Fanon’s formulation, “an underdeveloped middle class” with “practically no economic power.” This class was “not engaged in production, nor in invention, nor building, nor labour; it is completely canalized into activities of the intermediary type.” There was no bourgeoisie capable of shouldering national development. The task fell entirely on the state.

Nyerere’s developmental state thus became both the agency of national transformation and the site of accumulation. The public sector expanded rapidly, financed by draining surpluses from the peasantry and the underpaid semi-proletariat. State-run marketing boards—which Shivji identifies as “the great invention of the British after the Second World War to enable surpluses from the colonies to be accumulated in the metropolis to finance its reconstruction”—became the mechanism for siphoning surplus out of agriculture. The nationalist vision called for revolutionary transformation of economy and society, but the state that was supposed to carry out this transformation was itself colonial heritage: “a despotic state, a metropolitan police and military outpost, in which powers were concentrated and centralized, where law was an unmediated instrument of force.”

This is why Nyerere could celebrate Maji Maji and suppress its grammar simultaneously. The developmental state needed centralized accumulation. Dispersed cosmological authority threatened the very monopoly through which surplus extraction operated. The nationalist solution was epistemic appropriation: claiming Maji Maji as origin story while suppressing what made it threatening. The 1968 Maji Maji Research Project at the University of Dar es Salaam created the authoritative account emphasizing anti-colonial unity and heroic leadership—Maji Maji as the proto-nationalist moment leading inexorably to independence. Meanwhile, the living grammar was delegitimized as primitive regression. Traditional authorities were absorbed into state hierarchy or suppressed. Cosmological practices were relegated to “culture”—separated from politics, denied political legitimacy, made object of folklore preservation or elimination.

The suppression was simultaneously celebratory and destructive: monuments erected, schoolbooks written, the actual practice-knowledge driven underground. Yet it could not be eliminated because it operated through informal transmission resistant to bureaucratic control. Veterans remembered. Communities maintained knowledge. When crisis demanded reactivation, the grammar was available—carried by those who understood that alternatives existed even when official discourse denied them.

4. The Simba Rebellion, 1964–1965

Patrice Lumumba’s assassination in January 1961—murdered in Katanga, his body dissolved in acid, the coup backed by Belgium and the United States—installed the exemplary neocolonial regime. Shivji places the assassination within the broader Cold War structure: independence found Africa “in the midst of a cold war and faced with a rising imperial power, the United States of America, for whom any assertion of national self-determination was ‘communism’, to be hounded and destroyed, by force if necessary, by manipulation and deception if possible.” Lumumba was assassinated; Nkrumah was overthrown with CIA connivance. Across the continent, “radical nationalists, who showed any vision of transforming their societies, were routed through military coups or assassinations. A few who survived compromised themselves and became compradors.”

Mobutu emerged as strongman. Congo became the textbook case of what Shivji calls the compradorial path: formal independence masking continued extraction, African elites functioning as intermediaries for foreign corporate and governmental interests, maintaining the extractive structures of colonialism under the flag of sovereignty. The class that inherited state power was, as Fanon had diagnosed, “a little greedy caste, avid and voracious, with the mind of a huckster, only too glad to accept dividends that the former colonial power hands out to it,” incapable “of great ideas or of inventiveness,” and “already senile before it has come to know the petulance, the fearlessness or the will to succeed of youth.” Conspicuous consumption at home, stashing funds in foreign bank accounts, virtually no productive investment—the neocolonial state generated the conditions of its own illegitimacy.

When Gaston Soumialot was tasked with organizing rebellion in eastern Kivu, he faced the same problem Kinjikitile had faced sixty years earlier: how to mobilize marginalized populations against a militarily superior enemy that claimed to govern them. The answer came across Lake Tanganyika. Tanzanian advisors brought knowledge that had survived Nyerere’s nationalist appropriation: the practice of maji to protect warriors and mobilize resistance. The forces that emerged—the Simbas—were overwhelmingly young, mostly twelve to twenty, an age group colonialism and failed independence had devastated. They underwent ritual baptism, received dawa, observed prohibitions paralleling Kinjikitile’s: celibacy, honesty, bodily austerity, dietary restrictions. The formation provided what the neocolonial state could not: moral community, authorization for resistance, transformation of youth with no prospects into an effective fighting force.

The effects were dramatic. Government soldiers frequently fled without fighting. Forty Simba warriors captured Stanleyville from a 1,500-man garrison without firing a shot. By mid-1964, the rebels controlled half of Congo. But Western powers intervened—Belgian paratroopers deployed by American aircraft, white mercenaries from South Africa and Rhodesia. By late 1965, the rebellion was militarily crushed. Leaders fled to Tanzania. Yet Laurent-Désiré Kabila, one of the Simba commanders, maintained small insurgent forces near Lake Tanganyika for three decades. The grammar survived because it operated through dispersed knowledge transmission rather than institutional continuity.

5. Mai-Mai in Collapsing Kivu, 1990s–Present

By the 1990s, Mobutu’s regime had completed its transformation into pure predatory apparatus. But the collapse was not purely internal. Shivji documents how the structural adjustment programs imposed by the Bretton Woods Institutions across Africa systematically dismantled even the modest achievements of the developmental period. “Balancing budgets involved cutting subsidies to agriculture and reducing allocations to social programmes, including education and health. Unleashing the market meant doing away with protection of infant industries and rolling back the state from economic activity. The results of SAPs were devastating.” Social indicators—education, medical care, health, nutrition, literacy, life expectancy—all declined. Deindustrialization set in. What your average development analyst calls “state failure” in eastern Congo is the terminal stage of this process: not that the state withered naturally but that its developmental capacity was systematically destroyed from outside while its extractive capacity was preserved.

In eastern Kivu, the specific mechanisms of dispossession intensified. Mobutu’s 1973 land law made all land state property, destroying customary tenure. This was precisely what Shivji theorizes as the state standing “in the position of a landlord in relation to the peasant producer,” where “sovereignty and property merge in the state” and “extra economic coercion plays a central role in the process of peasant production.” Political elites seized vast tracts for personal ranching operations. After the 1994 Rwandan genocide, over a million refugees—including former genocidaires—flooded into Kivu. Youth faced total marginalization.

The ground-level economic reality producing Mai-Mai recruitment is what Shivji identifies as labour subsidizing capital—the structural inverse of the capitalist logic where labor-power exchanges at value. In disarticulated peripheral economies, “unable to survive on the land peasants seek other casual activities—petty trading, craft-making, construction, quarrying, gold-scrapping etc. Foreign researchers document and celebrate these ‘multi-occupations’ as diversification of incomes and the ‘end of peasantry.’ It is nothing of the sort. These are survival strategies, which at the end of the day mean that peasant labour super-exploits itself by intensifying labour in multiple occupations and cutting down on necessary consumption.” The youth who become Mai-Mai are not joining because they “lack alternatives” in the way the humanitarian and developmentalist discourse assume. They are already inside a system of super-exploitation that structurally cannot provide what it promises. The formation offers what the economic apparatus withholds: protection, status, participation in collective power.

The earliest militia formations in Kivu included groups composed substantially of Simba veterans. When violence escalated in 1993, traditional chiefs sought out these veterans as custodians of the protective medicine tradition. New fighters were initiated through scarification, medicinal preparations pressed into wounds, bodies doused with ritually treated water. The behavioral requirements were extensive: prohibitions on sexual contact, theft, certain foods, washing with soap. Medicine men known as docteurs prepared each unit for battle. When government troops heard of Mai-Mai approach in 1996, they fled—the same pattern as 1964, the same pattern as 1905.

Today, dozens of Mai-Mai groups operate across Kivu. Their fragmentation is not organizational failure but structural characteristic: dispersed networks coordinating without centralized command, different docteurs preparing medicine according to local variations, different commanders maintaining autonomous authority, all participating in shared grammar. They fight against Rwandan-backed rebels, Ugandan insurgents, their own predatory national army, and—since 2000—a new regime of power: humanitarian intervention, which classifies them as “armed groups” requiring demobilization. Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) programs consistently fail because they address consequences while ignoring causes. Fighters join not because they lack individual economic alternatives but because the formation provides what institutional frameworks cannot—protection when state authority is absent, collective capacity when individual advancement is blocked.

6. The Longue Durée

Seen across 120 years, the pattern is clear. Each regime of modernizing power assumes legitimate sovereignty must flow through centralized institutions. Each encounters a formation that organizes sovereignty through cosmological alignment, dispersed networks, and ritual discipline. Each attempts elimination through combined military and epistemic violence—destroying the practice while appropriating or dismissing its meaning. Each fails because it cannot provide what it claims to monopolize: actual protection for the populations it claims to serve.

Shivji’s analysis of accumulation reveals the economic mechanism ensuring this failure is structural rather than contingent. The disarticulated economy answers to accumulation crises at the center, not to the needs of its own population. Agriculture generates surplus but does not accumulate it—surplus is extracted through compradorial intermediaries and siphoned to the imperial metropoles. Industry exists as an enclave bearing little relation to agriculture. The home market is “virtually destroyed as even staple foods like flour, oil, potatoes, tomatoes, vegetables, etc. are imported from outside by supermarket chains to the detriment of small domestic producers.” As Alain de Janvry summarizes: “The key difference between social articulation and disarticulation thus originates in the sphere of circulation. Under social articulation, market expansion originates principally in rising national wages; under disarticulation, it originates either abroad or in profits and rents.” Every regime inherits this disarticulated structure. None can provide genuine protection because the economy is not organized to serve those it claims to govern.

The key structural insight is that each suppression creates the conditions ensuring return. German colonialism destroyed protective systems while imposing the forced labor that demanded them. Nationalist appropriation celebrated Maji Maji as origin while suppressing its living grammar, yet could not eliminate practice-knowledge transmitted informally outside bureaucratic channels. Neocolonial clientism created the total state failure that reactivated the formation in its most dramatic form.

Extra-colonial humanitarian intervention now reproduces the same incomprehension in new language. Where colonialism saw “primitive superstition” and nationalism saw “obstacles to modernization,” humanitarian discourse sees “negative forces” requiring management. A senior British diplomat, Robert Cooper, has articulated the underlying philosophy with remarkable candor: “The challenge of the post-modern world is to get used to the idea of double standards. Among ourselves, we operate on the basis of laws and open cooperative security. But when dealing with more old-fashioned kinds of states outside the post-modern continent of Europe, we need to revert to the rougher methods of an earlier era—force, pre-emptive attack, deception, whatever is necessary to deal with those who still live in the nineteenth century world.” Cooper names this “a new kind of imperialism, one acceptable to a world of human rights and cosmopolitan values,” operating through “the voluntary imperialism of the global economy” via the IMF and World Bank. The cycle continues because the regimes that suppress the formation are the same regimes whose failures create the crises demanding collective response.

My perspective is that this is not three or four separate rebellions sharing symbolic resonance. It is one regional formation, one recurring grammar transmitted across Lake Tanganyika and throughout the interlacustrine world, one mode of sovereignty that has outlasted German conquest, survived nationalist appropriation, persisted through neocolonial extraction, and continues operating despite extra-colonial international peacekeeping and development intervention. It persists not because populations are manipulated or backward or refusing progress, but because the grammar functions when alternatives fail—and alternatives have been failing, in this region, for 120 years.

Wider Stakes

The Long Maji Maji belongs to a global pattern. Between 1890 and 1910, similar formations emerged wherever populations faced apocalyptic violence with massive military disadvantage: the Ghost Dance across North American Plains nations in 1890, the Boxer Rebellion in northern China from 1899 to 1901, Maji Maji in German East Africa from 1905. All three were militarily crushed. All three were dismissed as primitive superstition. I have attempted to demonstrate here that the dominant account is false for Maji Maji. Whether Ghost Dance or Boxer formations have similarly persisted, transformed, and reactivated under new conditions—that work must be done by those who carry the knowledge.

But what the Long Maji Maji demonstrates is this: the national question and the agrarian question—what Shivji identifies as the fundamental unresolved contradictions of peripheral capitalism—remain open. These questions are “inseparably linked and inserted in the global process of imperialist accumulation,” which produces “articulated accumulation at the centre and disarticulated accumulation at the periphery.” Under disarticulated accumulation, “capital shifts the burden of social reproduction to labour, thus neither the peasant nor the proletarian labour is fully proletarianised.” The dominant tendency is semi-proletarianization, in which the worker “super-exploits himself/herself by cutting into his/her necessary consumption—a form of accumulation by dispossession.” The formation activates precisely in the gap between what peripheral capitalism extracts and what it refuses to provide. As long as the economy is organized to generate surplus it cannot accumulate, to serve centers it cannot reach, to depend on institutions that cannot protect—the grammar will persist.

Sovereignty organized outside state frameworks has never been eliminated despite more than a century of sustained suppression across fundamentally different political regimes. Modernizing power’s claimed necessity is contingent, its forms particular, its alternatives persistent. Until it can recognize cosmological authority as legitimate rather than primitive, dispersed networks as political rather than criminal, ritual discipline as governance rather than superstition—the Maji Maji formation will continue its pattern of transmission and return. Not as failure. As evidence that when regimes claiming monopoly on legitimate violence repeatedly fail to protect, populations will turn to what works.

Selected Sources

Eriksson Baaz, Maria, Judith Verweijen, and Jason Stearns. "The National Army and Armed Groups in the Eastern Congo: Untangling the Gordian Knot of Insecurity."

Giblin, James, and Jamie Monson, eds. Maji Maji: Lifting the Fog of War.

Jourdan, Luca. "Mayi-Mayi: Young Rebels in Kivu, DRC."

Malekela, Samson Peter. "In Pursuit of Continuity: Maji Maji War and Nationalistic Movement in 1940s-1950s in Southern Tanganyika."

Prunier, Gérard. Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe.

Shivji, Issa G. Accumulation in an African Periphery: A History of Labour and Livelihood in Tanzania.

Shivji, Issa G. Class Struggles in Tanzania.

Wild, Emma. "'Is It Witchcraft? Is It Satan? It Is a Miracle': Mai-Mai Soldiers and Christian Concepts of Evil in North-East Congo."