Merikani

Empire survives by shelving the world into separate volumes: Atlantic slavery over here, Indian Ocean trade over there, Africa filed later as a “development problem.”

Merikani refuses the shelf.

In nineteenth-century East Africa, enslaved people were often garbed in the rudest, cheapest white cotton cloth, called merikani because it came from the United States. Cotton grown under plantation slavery in the Americas moves as fiber into British and American mills, where industrial machinery turns it into low-cost cloth. Then it moves in Indian Ocean circuits — Zanzibar, Bagamoyo, caravans inland, the Gulf — showing up as payment, clothing, currency, lubricant. The Atlantic motor drives the Indian Ocean teeth.

And when I say, “I am the offspring of the Third Scramble for Africa and the Fourth Wave of Euro-Amerikaner Settlement,” merikani makes that sentence stop sounding like metaphor. It shows how the First Scramble doesn’t simply precede later systems; it feeds them. Cheap cloth is the residue of one regime becoming the lubricant of another.

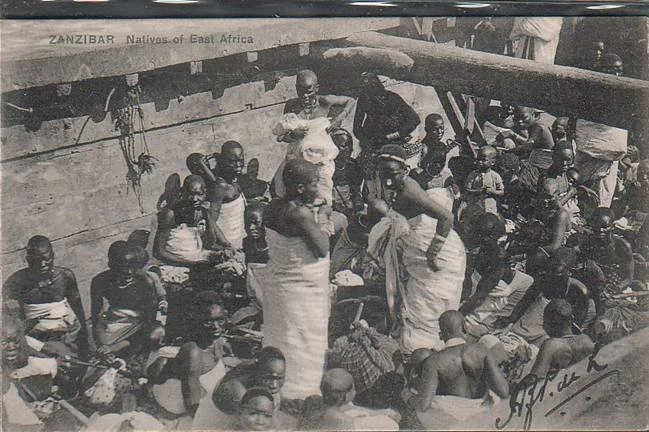

A slave gang in Zanzibar garbed in merikani cloth,1868. Drawing by WA Churchill.

Merikani looks like nothing special. Coarse cotton, often striped, cheap enough to ship by the bale. In drawings and photographs it sits like background noise: cloth wrapped around bodies, folded on market stalls, used as sheeting, traded without ceremony. But when I follow its path, it stops being background. It becomes a diagram of how different oceans were stitched into one economy.

Here’s the route in plain terms. The cotton begins in the Americas, first under plantation slavery, then under neo-slavery and sharecropping. It moves as fiber into British and American mills, where industrial machinery turns it into cheap cloth. That cloth enters Indian Ocean trade, arriving at ports like Zanzibar and Bagamoyo, circulating inland via caravans, and moving north and east into the Gulf, where it shows up on boats, plantations, and in households.

The reason this matters to me is that it makes one claim hard to dodge: the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds were never separate stories. The same industrial system that spun cotton picked by enslaved people supplied cloth used to pay porters, clothe captives, and lubricate trade in ivory and people across East Africa and into Arabia. Merikani isn’t the whole story, but it’s the connective object that refuses to let us tell the story in clean regional boxes.

Ivory played a parallel role, turning African labor into European wealth. Enslaved porters, dressed in merikani, carried tusks across hundreds of miles to coastal markets like Zanzibar, where they were sold to European and American buyers. Those tusks, transformed into piano keys, combs, buttons, handles, and ornaments, concealed the suffering of the people who moved them. Porters yoked and burdened with tusks weighing over 100 pounds died in droves along the way to coastal hubs. Accounts describe these journeys as a treadmill of exhaustion where death was constant. The ivory they carried enriched towns like Deep River, Connecticut, a center of ivory processing. Each piano key and luxury ornament bore the unseen imprint of their suffering, embedding violence in the everyday objects consumed by distant markets.

All of this also forces a second claim into view, one that doesn’t flatter anyone’s favorite timeline. Capitalism did not invent contempt for Black people. What capitalism did was reorganize contempt, standardize it, and turn it into finance, into scalable, portable value that can move faster than bodies and leave fewer fingerprints.

Before Portuguese caravels rounded the African coast, parts of the Arabic and Persian archive already described Blackness as deficit and treated African captives as a distinct category of enslavement. This goes back as far as the seventh century, when the king of newly Islamized Egypt inserted treaty clauses with neighbors requiring annual tribute in slaves from bilād al-sūdān (“land of the blacks”). By the ninth century, Arabic distinguishes between kinds of enslaved people with different implied uses and statuses, with the Black ’abd positioned as the lowest. Over time, Blackness and bondage lean toward each other in language and social practice until the association starts to feel “natural,” which is exactly how these systems like to present themselves.

And this isn’t just travel gossip. The archive includes respected scholars writing statements that circulate in elite networks. Ibn Ḥawqal can treat lands south of the Sahara as beneath notice because he “naturally loves” wisdom and order. Ṣāʿid al-Andalusī can claim climate scorches the people of the south and makes them unfit for science. Ibn Khaldūn can say bluntly that Black peoples are suited to slavery because they supposedly have little that is essentially human.

Alongside this sits theology. A version of the curse of Ham migrates across manuscripts and trade routes, linking Blackness and enslavement as fate and lineage, not just circumstance. Whether every reader believes it literally isn’t the point. The point is that it offers a ready-made explanation for why Black people can be treated as property. It’s a narrative patch that makes violence easier to route through law, commerce, and conscience.

And yet Islamic legal theory also contains a constraint that can, in principle, interrupt slavery: Muslims are not supposed to be enslaved; protected non-Muslims under Muslim rule are meant to be off limits; only outsiders captured in certain ways, or those born into enslaved status, can legally be held as property. On paper, faith and affiliation matter.

In practice, the frontier eats the paper.

Raiders cross lines scholars declare sacred. A ruler in Bornu can write to Cairo insisting his people are Muslim and entitled to protection, and still watch bodies from his realm sold in markets. Opinions are issued; protests go out; the trade continues. The rule bends around Black flesh.

I hold onto that gap, principle versus practice, because later, in East Africa, conversion to Islam becomes both faith and shield, both devotion and credential. Sometimes it works; often it doesn’t. But the fact that it is supposed to work creates a social opening that people on frontiers try to pry wider. The opening is narrow, but narrow openings still matter when the alternative is being processed as prey.

When I slide down the Swahili coast and up into the Gulf, I see a long history of African labor dug into soil and sunk into sea. In Abbasid Iraq, large numbers of Africans are worked on land reclamation; the Zanj rebellion of 869–883 — zanj from the Persian zang, meaning “black” — shakes the empire. Later, captives from East Africa and the Horn are absorbed into agriculture, fishing, boats, and military and domestic roles along Arabian shores.

By the nineteenth century, the Gulf is wired into global markets for dates and pearls. That wiring shifts the question from “what does Islam say about slavery?” to “what does the price of commodities do to labor demand?” When date and pearl markets spike, imports of African enslaved labor spike with them. The traffic is not “distinctly Islamic” in some cultural essence sense. It’s an economic response to global demand, routed through local hierarchies that already know how to treat Black bodies as expendable.

On pearl boats in the Persian Gulf, the labor system compresses slavery and capitalism into a routine: seasons lasting over a hundred days, divers dropping with stones, hauled up by rope, repeating until bodies break. Many divers are enslaved. Many “free” divers are trapped in debt because merchants advance supplies at predatory markups. Debts are recorded in ledgers divers often cannot read. On the same deck, one diver hands over wages to service debt; another hands over everything to a master who owns his body. Different legal statuses, similar exposure.

Then the system collapses not because conscience suddenly wins, but because the commodity regime changes. Japanese cultured pearls flood markets; Gulf pearling can’t compete. California dates undercut Gulf production. Revenues drop; enslavers turn people out because the asset is losing value. Manumission becomes common because liquidity evaporates.

That pattern — bondage expanding with boom, dissolving with bust — matters to me because it shows how quickly a human category can be produced, stabilized, and then “released” when markets shift. It also shows how legal freedom can arrive as a byproduct of economic revaluation without the underlying social hierarchy disappearing. Status lingers in the social firmware long after the official contract is revised.

But let’s rewind from the nineteenth-century Gulf to the fifteenth century, when Europeans begin raiding the Atlantic coast in earnest. They don’t step into a world with no existing association between Blackness and servility. They step into a field already shaped by older Afro-Eurasian slaving systems and racialized imaginaries.

What changes is organization.

The Iberian peninsula becomes one hinge. Under Muslim and Christian rule, enslaved populations are diverse around the Mediterranean, and Blackness is one indicator among others. As border wars stabilize and the old supply of captives dries up, Portuguese elites turn south and scale up. In the mid-fifteenth century, large cargos of Africans arrive in Portugal; chroniclers describe them with open dehumanization. Over a few decades, the association flips: Blackness increasingly implies slavery, and slavery increasingly implies Blackness.

There is a second hinge: conversion. In Islamic legal reasoning, however violated, conversion can in principle interrupt enslavement. In Iberian Atlantic racial thinking, especially once transplanted to the Americas, Blackness becomes recast as biological fate. No ritual, no education, no piety undoes it. Prejudices harden into proto-/psuedo-scientific doctrine.

And then capitalism does something crucial: it turns bodies into finance.

In the antebellum U.S., enslaved people become collateral for credit. Planters mortgage enslaved people to acquire shares, borrow against those shares, buy more enslaved people. Bonds backed by enslaved bodies circulate through global markets. Black life converted into liquid assets, into tradable, securitized financial instruments, made to look clean on paper. The contempt is old. Monetization is new.

This is the deep transformation merikani helps me see: a cheap commodity moving across oceans because a global system has learned to translate old hierarchies into scalable credit, into ledger entries that can travel farther than any person whose body made them possible.

So when I say merikani sits at a crossroads where American fields, European mills, East African coasts, and Arabian waters meet, I mean its job in the system is not symbolic but practical; it is exchanged, issued, worn.

Along routes into the interior, merikani functions as payment for porters. It dresses caravan labor. It circulates as currency to buy food, pay intermediaries, and acquire captives and ivory. On the coast, it can uniform enslaved labor. In the Gulf, it shows up on boats and plantations.

What’s more, merikani functions as an interface between status systems. The same cloth can mark servility in one context and respectability in another. That isn’t a contradiction; it’s how commodities behave. A commodity doesn’t carry one meaning. It carries meanings assigned within local hierarchies while still being moved by global price signals.

Women in Zanzibar wearing garments made from merikani cloth, some dyed.

That brings me to Lake Tanganyika and “interior ngwana,” where my mother’s line becomes legible inside the merikani/Islam/capitalism story rather than sitting beside it as a separate “family story.”

On my mother’s side, the story begins with Twa communities in the Great Lakes region — forest and wetland foragers across what is now eastern Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and western Tanzania. Over time, many were incorporated into Bantu agrarian societies, not as clean assimilation but as repositioning: hunters, diviners, performers, ritual specialists operating at the edges of settled life. The edge matters. It means vulnerability, yes, but it also means function, knowledge, and a kind of mobility within constraint.

Then the caravan economy expands. Routes that moved salt and cloth now move ivory and captives. Guns enforce corridors. Credit organizes followings. People are recoded: not primarily as kin or ritual specialists, but as categories with economic meaning — porter, captive, follower, client, slave-stock. The frontier becomes a living classification engine where labels decide who can be seized, who can move, who can claim protection, and who gets processed as inventory.

Along the shores of nineteenth-century Lake Tanganyika, coastal Swahili-speaking populations often describe interior people as shenzi. It’s an insult, but also a status assignment. It carries an assumption: interior peoples are of slave stock, which disqualifies them from being accepted as freeborn and/or Muslim in the coastal imagination. The opposite term is ngwana: coastal, civilized, respectable, inside the circle.

But in the interior, people start claiming ngwana status anyway. They become what scholarship calls “interior ngwana,” partly to distinguish them from coastal ngwana and partly because coastal populations often refuse to recognize their claims.

Interior ngwana are not invented out of thin air. They assemble a bundle of coastal cultural forms that are readable inland: Swahili language; rice preference; firearms; conversion to Islam; and merikani worn in the style of a kanzu. None of these elements alone is exclusive — Swahili is a trade lingua franca, rice and guns circulate widely, merikani is prized across regions. But the coalescence of all these features in one person becomes a recognizable profile inland: Muslim, respectable, ngwana.

This is where merikani lands directly in my mother’s history. In the interior, merikani is not primarily a “slave uniform.” It is a valuable good, a marker of coastal affiliation, part of the material grammar of respectability. Wearing it as kanzu is legibility in a frontier economy where being misread can get you captured.

Conversion to Islam sits in the same bundle. It can be protection strategy, alliance technology, and faith. It builds trust between coastal traders and interior followers. Trust matters because those followers are used in high-stakes roles as soldiers and proxy traders handling guns and credit. You don’t hand a firearm or a line of credit to someone you consider disposable unless you have mechanisms to secure loyalty. Islam and ngwana status become part of that mechanism.

This is structural story about how coercive systems create narrow lanes of survivability, then demand that people reshape themselves to fit those lanes.

And it’s why interior ngwana status should not be confused with freedom. Many interior ngwana remain in bondage voluntarily because attachment provides access to land, protection, and credit. Their claim to “freeborn” status often functions less as technical legal fact and more as a demand: treat me as respectable, not as prey.

This is where “Manyema” becomes more than a demographic label in my mother-line. The Manyema diaspora into what is now Tanzania occurs roughly from the 1860s into the early twentieth century. But in the precolonial period, those Manyema who became part of coastal traders’ followings often avoided the label Manyema and claimed ngwana instead.

The reason is plain: people east of Lake Tanganyika accused the Manyema of cannibalism. That accusation is a dehumanizing device. It removes people from the moral universe and helps justify violence. It functions like shenzi talk on the coast: a classification that authorizes predation.

So claiming ngwana is risk management in a world where names are weapons. Later, under colonial administration, “Manyema” can be re-appropriated and partially detached from the cannibalism stigma because the state re-files identity categories and redistributes stigma through bureaucracy. But the earlier moment matters because it shows a repeating pattern: my mother-line learns to move through labels to avoid being trapped in the worst one.

One reason interior ngwana conversions are easy for outsiders to misread is that Islamic practice on Lake Tanganyika’s shores is entangled with local religious frameworks, especially beliefs in nature spirits of the lake. These beliefs predate Muslim arrival and are linked to political authority: spirits demarcate the regional scope of chiefs’ power over shoreline zones. Different groups have different names: ngulu among Tabwa, amaléza among Fipa, ibisigo or mashinga among Jiji. Spirits are believed to control storms and sometimes take the form of crocodiles or hippopotami who “devour” those with whom the spirit is disgruntled. Appeasement involves canoe construction, pre-launch rituals, and sacrifice of valuable goods at spirit sites such as Kabogo point, Karema, and the north end of the Ubwari peninsula in eastern Congo where my mother’s family narrates its origins

Muslims and interior ngwana adapt coastal categories and practices into the lakeshore environment. The Swahili term zimu/mizimu becomes increasingly prominent in conceptualizing spirits. Interior ngwana appear to sacrifice imported beads and merikani cloth, coastal goods rather than livestock and crops. Coastal traders paint protective oculi on lacustrine craft, echoing Indian Ocean dhow practices. These are not random superstitions. They are cultural transfers moving along the same routes as cloth, guns, and credit.

If I’m placing my mother’s line historically, this matters because it makes conversion legible as a frontier process. In the absence of mosques, literacy, and opportunities to go on Hajj, “the coast” becomes the reference point for Islam. Coastal material and spiritual phenomena become templates. The result is a lived Islam that can be orthodox in some practices, like diet, fasting, prayer, but also heterodox by the standards of coastal elites and European observers. Coastal elites can call it blasphemous; Europeans can call converts “slaves,” which, if accepted, would bar them from being Muslim according to Islamic law. Both moves are convenient ways to deny interior people full moral standing.

So Islam here is also part of an inland struggle over status, protection, and legitimacy, and that struggle is carried by material goods like merikani as much as by doctrine.

From the early 1880s, armed stations and routes expand around Lake Tanganyika. Soldiers are armed with guns, used to subdue populations, and left to govern trading stations like Rumonge, Chumin, and Mtowa. These armed men declare themselves ngwana and raid for captives, ivory, and food, making their positions self-sufficient. Their successes let them dominate regions militarily, expanding both their own power and the commercial reach of the networks they’re entangled with.

Over time, it becomes more accurate to describe some as associates rather than slaves or laborers because they gain independent agency, attract followings, and become political actors on the lakeshore. And this is the part I have to hold without moralizing: the same process that offers some interior people a path out of prey status can also recruit them into the machinery of extraction and violence. Status ascent inside a frontier economy often means becoming an operator in the same system that once endangered you.

This dynamic is not separate from capitalism. It’s one of capitalism’s common frontier patterns: intermediaries emerge where violence meets trade, and they are rewarded with status and goods so the circuit can keep moving.

If I pull the camera back, merikani is an anchor object that keeps my mother’s line inside a single integrated world-economy. Cotton picked under Atlantic slavery becomes industrial cloth; cloth becomes currency in East African caravans; caravans expand Islam-as-credential inland; Islam and coastal forms become a survival bundle; shenzi/ngwana classifications become a gate that decides respectability versus prey; Manyema stigma forces strategic naming; inland Islam becomes both practice and contested legitimacy; guns and credit accelerate a shift from laborer to associate. And through all of it, the same basic mechanism repeats: taxonomies decide exposure.

Putting my mother’s line inside this history means naming the practical historical problem my ancestors faced and the strategies they used.

They moved through a frontier where coastal categories (shenzi/ngwana) could justify capture and exclusion. They assembled legibility through a bundle: Swahili, Islam, rice, guns, and merikani worn as kanzu. They navigated stigmas like “cannibal” and “savage” by changing names when names became cages. They lived Islam as both practice and alliance technology under conditions where coastal elites and Europeans had incentives to deny their legitimacy. They shifted as commodities shifted, from caravan trade to mineral circuits, without ever stepping outside coercion.

Sources

Gooding, Philip. On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, c. 1830–1890.

Hopper, Matthew S. Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire.

Suzuki, Hideaki. “African Slaves and the Persian Gulf.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History (School of Global Humanities and Social Sciences, National Museum of Ethnology).

“The Iberian Roots of American Racist Thought” James H. Sweet