World-Making

An introduction to the the (De-/Re-)Constructing Worlds project.

I.

The artist makes sensations in a given world — the artist composes sights (visual sensations), sounds (aural sensations), smells (olfactory sensations), tastes (gustatory sensations), touches (tactile sensations), etc.

The philosopher makes conceptions of a given world — the philosopher establishes the significance, the whither and wherefore, of different sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, etc.

The scientist makes predictions about a given world — the scientist figures out whether it is likely and how likely it is to encounter different sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, etc.

But neither the artist, nor the philosopher, nor the scientist can be said to make a world — for the making of a world precedes, exceeds, and succeeds the making of sensations, conceptions, and predictions.

The world that we come to sense in and through art, and to conceive of in and through philosophy, and to make predictions about in and through science is a world that is taken as a given by the artist, philosopher, and scientist; it is not a world that they make themselves in and by doing art, philosophy, or science.

Relations are what make worlds, which is to say, in other words, that making a world means making relations.

Sensations, conceptions, and predictions articulate the relations that precede, exceed, and succeed them. The figure of the artist enables us to sense established relations, the figure of the philosopher enables us to conceive of established relations, and the figure of the scientist enables us to make predictions about established relations, but none of these figures actually establish relations themselves. Establishing relations is an extra-artistic affair for the artist, an extra-philosophical affair for the philosopher, and an extra-scientific affair for the scientist.

A world-making project is neither an artistic project, nor a philosophical project, nor scientific project. Rather, a world-making project is the condition for artistic, philosophical, and scientific projects. Artists, philosophers, and scientists who cannot take the world that conditions their practices for granted find that they must act as world-makers in addition to acting as artists, philosophers, and scientists: they find that they must make the worlds that others will take as given.

II

Only the most privileged artists, philosophers, and scientists working in our time can take their world for granted. The world news of today is always bleak — global apartheid driving planetary ecocide — but don’t get it twisted: it is not our world that is dying. Rather, it is our world that is killing us: the world that we have made, some willingly but most unwillingly, is poised to destroy the greater part of life as we know it. Our arts give us a visceral sense of this deathly reality, our philosophies enable us to thoroughly conceive of this deathly reality, and our sciences enable us to predict this deathly reality with certainty. Ay, but our arts, philosophies, and sciences can do nothing in and of themselves to stop the unfolding of this deathly reality. This is because art-qua-art, philosophy-qua-philosophy, and science-qua-science cannot, in and of themselves, make a better world.

The deconstruction of the world that is putting an end to life and the (re-)construction of worlds in which life can thrive is an extra-artistic, extra-philosophical, and extra-scientific affair. Better art, better philosophy, and better science in and of themselves will only better our awareness of the catastrophe that is the world that we have made. To escape this catastrophe, we need better relations first, foremost, and above all else. Which is to say, in other words, that better art, better philosophy, and better science will either be the consequence of better relations or they will not be at all.

To do art, philosophy, and science alone is to do no more than run diagnostics on our relations. Running diagnostics and treating an illness are not at all the same thing. Refusing to invest in art, science, and philosophy means being unable to diagnose the ills of our relations, but investing in art, philosophy, and science without regard for world-making will do nothing to treat the ills of our relations. It seems to me today that the diagnosis is in and has been in for a half century, if not five centuries What we need now is to treat the ills of our relations: to further refine the diagnosis without regard for a treatment is dithering.

It is no wonder that many artists, philosophers, and scientists today are finding themselves called to be world-makers first and to be artists, philosophers, and scientists second. Which is to say, they are finding that they must put more time and energy into making relations and less into making sensations, conceptions, and predictions.

III.

So, what is a relation and how does it differ from a sensation, a conception, a prediction?

The wind whips across your face. You sense your face in relation to the wind, you sense the wind in relation to your face, you sense a world in which the wind and your face are related.

This particular sensation of the wind whipping your face is but one expression of the world in which the wind and your face are related. This one expression of this relation does not exhaust the relation. The sensation of the wind gently caressing your face is another, different expression of the world in which the wind and your face are related.

The world in which the wind and your face are related is the set of all the different possible sensations of the-wind-in-your-face/your-face-in-the-wind, of which the whipping wind and the caressing wind are but two of the possible sensations making up the set.

The act of world making is the act that opens up or forecloses a set of possible sensations.

The artistic act, the act of making of sensations, is the act of exploring a given set of possible sensations by realizing some of its possible sensations

The philosophical act, the act of making of conceptions, is the act of establishing priorities, deciding which sensations to realize from a given set of possible sensations and in what order to realize them.

The scientific act, the act of making of predictions, is the act of figuring probabilities, the act figuring out the likelihood that certain sensations within a set of possible sensations will be actualized.

IV.

Whether begrudgingly or exuberantly, no artist is exempted from doing philosophy and science, no philosopher is exempted from doing art and science, and no scientist is exempted from doing art and philosophy.

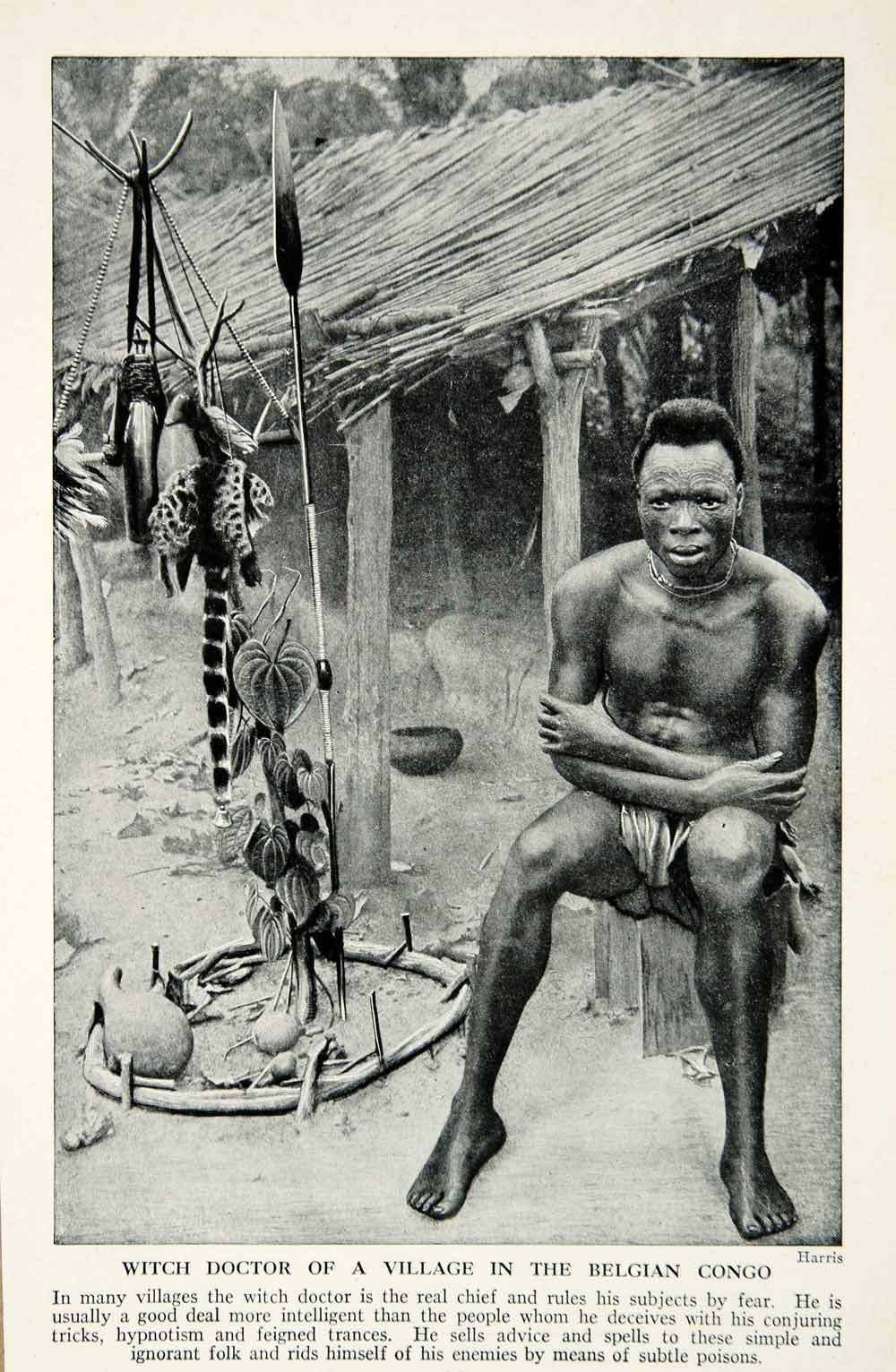

Indeed, before specialization made us believe that art, philosophy, and science could be separate and distinct disciplines, the artistic act, the philosophical act, and the scientific act were often performed together, with a single fluid gesture, by ritual figures like that of the medicine man, the oracle, the shaman, and the witch.

The specialization of the artist, the philosopher, and the scientist in our time is responsible for the mistaken impression, held by many, that art, philosophy, and science are practices that can make worlds in and of themselves. In our world, those who have been made to specialize in the different disciplines must compete for scarce resources, and this competition compels them to claim that their own specific discipline is the one that grounds all the others. The specialist in art is compelled to claim that art grounds philosophy and science; the specialist in philosophy is compelled to claim that philosophy grounds art and science; and the specialist in the sciences is compelled to claim that their science grounds art and philosophy. What gets lost in these competing claims is the practice of world-making, which is the proper ground of art, philosophy, and science. It is when the artistic act, the philosophical act, and the scientific act are performed together, with a single fluid gesture, that we realize that we must find the ground of art and philosophy and science elsewhere in world-making.

The act of world-making is the act of making of statements (“epistemic relations”), making of implements (“technical relations”), and making of environments (“territorial relations”) that taken together condition the making of sensations, conceptions, and predictions.

Figures like the medicine man, the oracle, the shaman, and the witch tend not only to act as artists, philosophers, and scientists at the same time but, more profoundly still, these figures tend to act as world-makers first, foremost, and above all else — making statements, implements, and environments together, with a single fluid gesture, prior to making sensations, conceptions, and predictions with a subsequent gesture. The “charms” of the medicine man, the oracle, the shaman, and the witch are the “sleights of hand” in and through which their primary world-making gestures deftly anticipate the secondary gestures with which they make sensations in, conceptions of, and predictions about the worlds that they make.

Today, as many who previously specialized in art, philosophy, and science find themselves called to be world-makers first and to be artists, philosophers, and scientists second, it is no wonder that many are coming to regard the “charms” of medicine men, oracles, shamans, and witches with less prejudice and incredulity and with more wonder and appreciation.

V.

The makings of statements, implements, and environments together constitute the makings of worlds.

A statement, or “epistemic relation”, is a set of possible senses of understanding.

Art realizes different senses of understanding, philosophy prioritizes different senses of understanding, science figures the likelihood of realizing different senses of understanding, but art, philosophy, and science always take certain statements as given in doing so.

The making of statements — the act of world-making which opens up or forecloses different possible senses of understanding — is an extra-artistic, extra-philosophical, and extra-scientific affair. World making gives us statements rather than taking them as given.

An implement, or “technical relation”, is a set of possible senses of affordance.

Art realizes different senses of affordance, philosophy prioritizes different senses of affordance, science figures the likelihood of realizing different senses of affordance, but art, philosophy, and science always take certain implements as given in doing so.

The making of implements — the act of world-making which opens up or forecloses different possible senses of affordance — is an extra-artistic, extra-philosophical, and extra-scientific affair. World making gives us implements rather than taking them as given.

An environment, or “territorial relation”, is a set of possible senses of place.

Art realizes different senses of place, philosophy prioritizes different senses of place, science figures the likelihood of realizing different senses of place, but, art, philosophy, and science always take certain environments as given in doing so.

The making of environments — the act of world-making which opens up or forecloses different possible senses of place — is an extra-artistic, extra-philosophical, and extra-scientific affair. World making gives us environments rather than taking them as given.

Take for instance, the laboratory of a scientist, which is one world amongst others. Before the scientist can conduct science there, the world of the laboratory has to be made in and through the making statements, implements, and environments. The lab of the biologist is a different world from that of the physicist, that of the computer scientist, and that of the trans-disciplinary scientist who does biology, physics, and computer science. These four different scientists take different worlds for granted when doing science. Perhaps the interdisciplinary scientist takes less for granted than the biologist, physicist, and the computer scientist but there is still much that the interdisciplinary scientist takes for granted.

What people call the “difference between the laboratory and the real world” is a misnomer because the world of the laboratory is as real as any other. The “difference between the lab and the outside world” is perhaps a little less of a misnomer, but it is still a misnomer because there is more than one world outside of the laboratory. We should instead speak of the difference between the world of lab and the plurality of worlds outside the lab. The plurality of worlds outside the lab are no less constructed than the world of the lab: the plurality of worlds outside of the lab are composed of statements, implements, and environments, like the lab but different. Indeed, what differentiates lab results from “real world” results are the differences between those statements, implements, and environments that compose the lab and those that compose worlds outside of the lab.

My point here is twofold: (i) the construction of the laboratory is the construction of a world in which a certain scientific results can be achieved and (ii) achieving a scientific result outside of the laboratory means constructing worlds outside of the laboratory that are more and more like the world of the laboratory.

The scientist who is deeply concerned with doing science in worlds outside of the lab is the scientist who is called to be a world-maker first and a scientist second. The same could be said of the artist who is deeply concerned with doing art in worlds outside of the studio and of the philosopher who is deeply concerned with doing philosophy in worlds outside of the seminar room — such artists and philosophers are called to be world-makers first and artists and philosophers second.

But the call to make worlds should not simply be a call to make other worlds more and more like the world of one’s lab, studio, or seminar room. Rather, the call to make worlds should be the call to (de-/re-)construct the world of one’s lab, studio, or seminar room so as to prefigure worlds that one would like to (de-/re-)construct outside of one’s lab, studio, or seminar room.