The Shape of Things to Come

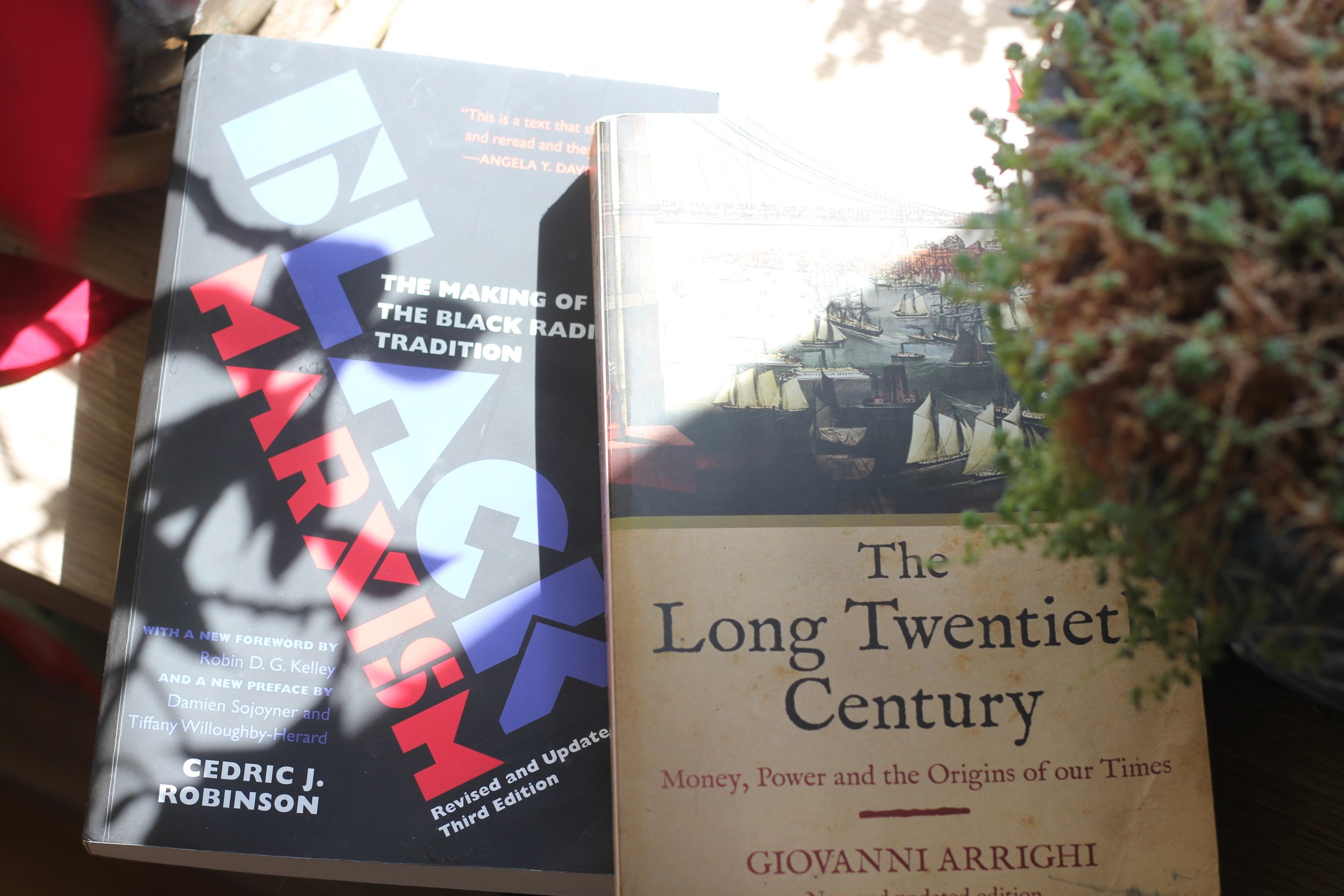

Reading Giovanni Arrighi’s Long Twentieth Century alongside Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism

Giovanni Arrighi’s Long Twentieth Century is the finest book that I have read on the dynamics of five centuries of capitalist imperialism. The book takes the reader on an epic journey through time: from the Long Sixteenth Century, the heyday of the Genoese-Iberian hegemony that laid the foundations for capitalist imperialism; to the Long Seventeenth Century, the heyday of the Dutch hegemony that brought the global capitalist joint-stock corporation into being; to the Long Nineteenth Century, the heyday of the British hegemony that transformed capitalist imperialism by and through doubling down on industrialization; and, finally, to the Long Twentieth Century itself, the heyday of the Amerikkkaner hegemony whose most unique characteristic was being more intentional about putting (capital “E”) Empire above (little “e”) empire, building international Imperial institutions (e.g., the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization) so that multi-national capitalist corporations could more effectively transform transaction costs from liabilities into assets .

The dynamics of capitalist imperialism described by Arrighi have been driven by capitalists’ need to “internalize” costs that were previously “externalized” in order to resolve crises of over-accumulation. The term “internalize” can be a tad misleading, however, as capitalists do not simply absorb the costs that they “internalize.” Rather, capitalists transform the costs that they “internalize” from liabilities to capital assets. Over-accumulation crises emerge whenever capitalists in possession of immense surpluses of money cannot find enough places to safely and profitably invest their surpluses. Over-accumulation crises are resolved when capitalists manage to find ways to safely and profitably invest their surpluses in enterprises that effectively transform externalities that were previously liabilities into capital assets.

The Genoese were cosmopolitan financial capitalists through and through — which is to say, in other words, that they externalized as many costs as they could: protection, production, transaction, and reproduction costs alike. The Genoese made their money by investing in the imperial enterprises of the Iberians (the Spanish and the Portuguese), receiving shares of the profits of successful imperial enterprises and earning fees and interest on debts owed to them no matter whether imperial enterprises succeeded or failed. Hence, the first period of capitalist imperialism, the Long Sixteenth Century, is known as the period of Genoese-Iberian hegemony: the Genoese were the capitalist hegemon, the Iberians were the imperialist hegemon, and the formation the Genoese-Iberian capitalist-imperialist alliance was, effectively, the founding act of capitalist imperialism.

The Dutch internalized the protection costs that the Genoese had externalized; in so doing, the Dutch transformed the means and relations of organizing protection for imperialist enterprises from liabilities into capital assets. Whereas the Genoese capitalists needed the Spanish and Portuguese aristocratic imperialists to protect the enterprises that they invested in; the Dutch East India Company, which was established in 1602 as the first joint stock company, was a capitalist imperialist enterprise that maintained military forces fully capable of protecting the enterprises that it invested in. This is to say, in other words, that the Genoese-Iberian alliance between capitalists and imperialists, as two separate factions, was overtaken by a unified faction of Dutch capitalist imperialists during the Long Seventeenth Century.

The British internalized the production costs that the Genoese and the Dutch had both externalized; in so doing, the British transformed the means and relations of organizing global production from liabilities into capital assets. Whereas the leading Dutch capitalist imperialists profited mostly from financing and protecting the movement of goods manufactured all around the globe, the leading British capitalist imperialists also profited from organizing the industrial manufacture of goods all around the globe. This is to say that industrialization enabled British capitalist imperialists to profit from lowering the material, labor, and logistics costs of global production in addition to profiting from financing and protecting global supply-chains. What’s more, the leading British capitalist imperialists effectively established the imperialist nation-state as a protection services provider for capitalist imperialist enterprises, transforming the public financing of national debts into the financing of protection costs for capitalist-imperialist enterprises.

The United Settlers internalized the transaction costs that the Genoese, the Dutch and the British had all externalized; in so doing, the United Settlers transformed the means and relations of organizing global transactions from liabilities into capital assets. Whereas the leading British capitalist imperialists primarily profited from the industrial manufacture of goods and from financing and protecting global supply-chains, the leading Amerikkkaner capitalist imperialists profited just as much from the marketing of goods and complementary services around the globe. Marketing here includes “the selection of target markets; the selection of certain attributes or themes to emphasize in advertising; the operation of advertising campaigns; the design of products and packaging attractive to buyers; the definition of the terms of sale, such as prices, discounts, warranties, [consumer financing,] and return policies; the placement of products in media or with people believed to influence the buying habits of others; the negotiation of agreements with retailers, wholesale distributors, [franchisees,] and resellers; the organization of efforts to create awareness of, loyalty to, and positive feelings about a brand; etc.” What’s more, the leading Amerikkkaner capitalist imperialists also reimagined and reorganized the imperialist nation-state so that, in addition to being a provider of protection services, the imperialist nation-state also became a provider of social services that enabled and encouraged its subject populations to adopt a consumerist ideology and fit into a consumer society. The public financing of national debts under Amerikkkaner hegemony went beyond the financing of protection costs for capitalist imperialists, and included the financing of those transaction costs necessary for the maintenance of a consumer society that no individual imperialist capitalist enterprise could bear on its own.

After laying out the history summarized above, Arrighi’s book goes on to suggest that, if capitalist imperialism is to survive the over-accumulation crises that are presently threatening it, capitalist imperialists will now need to find ways to internalize “reproduction costs” that they have previously treated as externalities. The term “reproduction costs” refers to the costs of sustaining cultural and natural resources, and contemporary capitalist imperialists’ new found concern for “sustainable development” is primarily about transforming the costs of sustaining cultural and natural resources from liabilities into capital assets.

Lest you think that this new found capitalist concern for “sustainable development” bodes well for culture and nature, let me make something clear to you. Every capitalist endeavor to internalize costs previously considered externalities has, thus far, been an ethnocidal and ecocidal endeavor: the more costs capitalist imperialists internalize, the more capitalist imperialism takes hold of life and squeezes out those parts of life that do not yield any profits. If capitalist imperialists can successfully internalize the costs of sustaining cultural and natural resources, capitalist imperialists can refuse to sustain those aspects of culture and nature that do not yield profits for them and they can choose to sustain only those aspects that do yield profits for them.

Attempts to sustain that which is profitable about culture and nature will be celebrated as a “moral achievement” by capitalist imperialists given that, heretofore, capitalist imperialists had only ever exploited cultural and natural resources with little concern for sustaining these resources for future generations. Ay, but this “moral achievement” by capitalist imperialists will, in fact, be a cultural and natural catastrophe: promoting global Sustainable Development Goals that diminish all that is unprofitable about culture and nature effectively means promoting ethnocides and ecocides of an unprecedented scale and scope in order to privilege the proliferation of that which is profitable. The onus will be on marginal peoples and marginal places to demonstrate to capitalist imperialists that they possess cultural and natural resources worth sustaining, either because they present profitable ecosystem services or opportunities for “social entrepreneurship.”

Going further and digging deeper, it is important to recognize that, historically, prevailing hegemons have found it difficult to resolve over-accumulation crises by internalizing externalities, while upstarts (i.e., “would-be hegemons”) have found it easier to resolve over-accumulation crises. This is because the prevailing hegemons do not experience over-accumulation crises as acutely as upstarts do. Prevailing hegemons are usually so powerful that they cannot only weather over-accumulation crises but, more profoundly still, prevailing hegemons can actually take great pleasure in exercising their dominance over others during over-accumulation crises. In fact, this is precisely what hegemony is all about, and why it is sought after. Indeed, established hegemons have been known to aggravate over-accumulation crises in order to heighten the pleasure they take in dominating lesser powers during times of crisis. As a result, prevailing hegemons are unlikely to seize the initiative when it comes to resolving over-accumulation crises — that is, of course, not until prevailing hegemons observe upstarts effectively seizing the initiative and threatening to overtake them. By then, however, it is usually too late: the upstart who successfully seizes the initiative to resolve a crisis first, and who then effectively defends their seized initiative with military force, is usually able to demote the old hegemon and become the new hegemon.

During the transition from the Long Sixteenth to the Long Seventeenth Century, the Dutch seized the initiative from the Genoese by internalizing protection costs, and the Dutch successfully defended their seized initiative against the Genoese-Iberian alliance. That being said, however, the Dutch failed to defend their seized initiative against their allies in their wars against the Iberians, the British and the French. As Arrighi notes, “Dutch world hegemony was […] a highly ephemeral formation.” For most of the Long Seventeenth Century — from the outbreak of the Anglo-Dutch Wars in 1652 (a mere four years after the Settlement of Westphalia with the Iberians) to the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 — the British and the French were locked in competition to become the hegemonic power who would take over from the dwindling Dutch.

During the transition from the Long Seventeenth to the Long Nineteenth Century, the British seized the initiative by internalizing production costs, and they successfully defended their seized initiative against the French during the Napoleonic Wars. The British, unlike the Dutch, effectively dominated their Long Century, serving as the conductor and primary beneficiary of the “Concert of Europe”.

During the transition from the Long Nineteenth to the Long Twentieth Century, the Amerikkkaners and the Germans both managed to seize the initiative in internalizing transaction costs. However, whereas the Germans had to confront British hegemony directly as they seized the initiative, the Amerikkkaners were able to ally themselves with the British against the Germans. The Amerikkkaners effectively demoted the British and became the new hegemon after the World Wars fought against Germany had effectively exhausted the British and empowered the Amerikkkaners vis-à-vis the British.

It is important to note that the Germans were forced to confront the British directly because the Germans, unlike the Amerikkkaners, did not have an expansive territorial empire from which they could extract resources. As they sought to seize the initiative, the Germans found that they had to build an expansive territorial empire by seizing territories from and upsetting other imperial powers, including the British. The Amerikkkaners, by contrast, didn’t have to confront the British directly because the Amerikkkaners already possessed an expansive territorial empire. Arrighi quotes Gareth Stedman Jones on this point, “historians who speak complacently of the absence of the [imperialism] characteristic of European powers merely conceal the fact that the whole internal history of U.S. imperialism was one vast process of territorial seizure and occupation. The absence of territorialism ‘abroad’ was founded on an unprecedented territorialism ‘at home.’”

During the Long Twentieth Century, the Amerikkaners successfully secured and defended their hegemony not only against rival capitalist powers but also against rival anti-capitalist powers. The Amerikkaners have fought and “won” three world wars during the rise and tenure of the United Settler States as hegemon — two hot wars (World Wars I and II against German capitalist imperialists and their allies) and one cold war (the Global Cold War against Soviet communist imperialists and their allies). In and through the process of fighting these three world wars, the Amerikkkaners have amassed outrageous stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction and they have organized the means and logistics needed to deploy weapons of mass destruction almost anywhere on the globe at any time. This means that the Amerikkkaners can effectively threaten to destroy all life on Earth in an all-consuming conflagration before ever giving up hegemony.

Today, as over-accumulation crises abound and threaten to undermine Amerikkkaner hegemony, it is very likely that an upstart power might seize the initiative when it comes to internalizing reproduction costs, but it is very unlikely that an upstart power will be able to defend its seized initiative against the Amerikkkaners without provoking a war that cannot be won. The Amerikkkaners recognize this and, instead of seizing the initiative first and going all in on sustainable development, the Amerikkkaners are doubling down on military spending, further ensuring that any upstart power that manages to seize the initiative will never be able to successfully defend its seized initiative against them.

The threat of nuclear war is one game-changer in the capitalist imperialist competition to achieve world hegemony. The climate crisis is another. Chances are that we are not living through a phase change from a relatively stable climate regime that is cooler to another relatively stable regime that is hotter but, rather, that we are living through a phase change from a relatively stable climate regime to a chaotic climate regime. All the predictive models of political economy, all of the normalizing and optimizing powers of capitalist imperialism, assume that a relatively stable climate regime can be maintained. If we are entering a chaotic climate regime, all of these models will no longer be able to effectively normalize and optimize the global economy any longer: over-accumulation crises will become much more frequent and much more acute as it becomes harder and harder for capitalist imperialists to manage risks by exercising normalizing and optimizing powers that render the global economy predictable. It follows from this that it will become harder and harder for the leading hegemon, the United Settler States, to weather over-accumulation crises and, perhaps, this may spur them to buck the historical trend and seize the initiative first when it comes to internalizing the costs of sustaining cultural and natural resources. Admittedly, this does not seem to be the case at present, but the climate catastrophes have only just begun…

Now, having summarized Arrighi’s book, I must mention that there is one feature of Arrighi’s book that feels to me like a major flaw. His book helps us make sense of the forces driving the actions of capitalist imperialists, yes, but it doesn’t help us make sense of the forces driving the actions of anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists.

Arrighi’s book invites the reader to ask the questions that the most discerning capitalist imperialists are presently asking themselves… Will the Amerikkkaners hold on to their hegemony at any cost, even if that means nuclear war? Will the People’s Republic of China, the most powerful upstart power today, try to seize the initiative and make an aggressive bid for hegemony in spite of the overwhelming military might of the Amerikkkaners? Will an anti-China triple alliance of other upstart East Asian capitalist powers (composed of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) successfully join forces with the Amerikkkaners and their NATO allies to prevent China from achieving hegemony (in a manner similar to how the Amerikkkaners joined the British to prevent Germany from achieving hegemony)? If so, will the Amerikkkaners and their NATO allies, having pivoted to Asia, effectively become the imperial military muscle for the resulting capitalist hegemony of the East Asian triple alliance (in a manner similar to how the Spanish and Portuguese effectively provided the imperial military muscle for the capitalist hegemony of the Genoese)?

All very good questions, yes, but Arrighi’s book does not invite the reader to ask what I regard to be the most important question today… How can today’s anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists force a break with evolutionary patterns of world capitalism that have already inspired and shaped more than five centuries of increasingly devastating genocidal, ethnocidal, and ecocidal projects, and which are presently inspiring and shaping even more devastating genocidal, ethnocidal, and ecocidal projects?

Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism covers the same epic five-century time-span as Arrighi’s Long Twentieth Century but, instead of focusing on the forces driving the actions of capitalist imperialists, Robinson focuses on the forces driving the actions of the anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists of the Black Radical Tradition. In so doing, Robinson’s work invites the reader to ask how today’s anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists might force a break with the evolutionary patterns of world capitalism by learning from the successes and failures of the many different anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist traditions to which they are heirs.

The astute reader of Robinson’s book will realize three things.

First, the reader will realize that escape, fugitivity, desertion, and marronage are some of the powerful but under-appreciated forms of resistance to imperialism and capitalism, and there are incredible traditions of such resistance that we might learn from. Indeed, given that all direct confrontations with and amongst capitalist imperialists today revolve around the prospects of one party using weapons of mass destruction against their rivals, potentially turning Life on Earth into collateral damage, it seems to me that escape, fugitivity, desertion, and marronage are simultaneously the most powerful and least reckless forms of resistance available to anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists today.

Second, the reader will realize that escape, fugitivity, desertion, and marronage have been the conditions of possibility for the emergence of many other forms of anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist resistance. Escape, fugitivity, desertion, and marronage have, historically, created the time and the space for anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists to conduct experiments in organizing alternative economies and ecologies that were, in Robinson’s words, “beyond the comprehension and control of the [capitalist imperialist] master class.”

Third, the reader will realize that anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist experiments in organizing alternative economies and ecologies should be about (i) recovering the more or less fragmented remnants of cultures that have been subjected to erasure by the advance of capitalist imperialism, (ii) piecing these remnants together, and (iii) (re-)creating these cultures anew. It is a mistake to think that anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist movements have historically been about putting outmoded cultures behind us and constructing brave new worlds. Rather to the contrary, the forces driving the actions of anti-imperialists and anti-capitalists have, more often than not, been the forces that inspire people(s) to remember cultures that have been lost to and destroyed by the advance of capitalist imperialism. Eurocentric Marxisms often fail to grasp this fact insofar as they refuse to look backward and make amends with the past and, instead, choose to focus on forward looking ideals of the “Communist man” as “man of the future.” Indeed, Robinson’s book turns on Eurocentric Marxisms’ refusals to recognize the Black Radical Tradition’s concern with (i) recovering the remnants of African cultures that have been subjected to erasure by Euro-Atlantic capitalist imperialists and (re-)creating these African cultures anew.

Afro-futurism, to the degree that it is a spin-off of the Black Radical Tradition, differs from Eurocentric futurism in that it is about (re)creating the African past anew. Afro-futurist works describe and depict futures in which remnants of past African cultures — remnants of African cultures that have been subjected to erasure by Euro-Atlantic capitalist imperialism — are recovered and pieced together in order to (re-)create them anew. In the process of being recovered, repaired, and (re)created anew, these past African cultures are inevitably transformed in such a way that they are no less futuristic than any product of the Eurocentric futurist imagination.

If Eurocentric futurist works are less lively than Afro-futurist works, it is because Eurocentric futurist works assume that cultures that have been subjected to erasure by Euro-Atlantic capitalist imperialism are cultures that are never to be recovered, meaning that the future must be the product of processes of cultural selection and curation that are governed by modern Euro-Atlantic sensibilities. How boring!

Afro-futurist works focus on the (re-)creation of past African cultures anew, yes, but the liveliness of Afro-futurist works arises from the fact that Afro-futurist works effectively assume that ALL of the different cultures subjected to erasure by Euro-Atlantic capitalist imperialism may be recovered and (re-)created anew, not just the pre-modern African cultures but also the pre-modern Asian cultures, the pre-modern Oceanian cultures, the pre-modern New World Indigenous cultures, and the pre-modern matriarchal pagan cultures of Europe.

The Black Radical Tradition is extremely significant because Eurocentric white supremacy and anti-Black racism have been part and parcel of Euro-Atlantic capitalist imperialism since its inception. Indeed, Eurocentric white supremacy and anti-Black racism persist to this day, in spite of the so-called “abolition” of slavery during the late nineteenth century, and they still continue to contribute to the maintenance and advancement of capitalist imperialism. It is true that as the capitalist imperialist struggle for hegemony has pivoted from the Euro-Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific region, the prevalence of Euro-centric white-supremacy has been attenuated to some degree. However, anti-blackness has not been attenuated to nearly the same degree. Indeed, despite the ongoing pivot from the Euro-Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific, race is poised to continue to serve as capitalist imperialism’s epistemology, ordering principle, organizing structure, moral authority, and economy of justice, commerce, and power.

Arrighi does not dwell on the racialized Atlantic slave trade in his book, but Arrighi does note (i) that the Genoese financed and the Iberians operated the racialized Atlantic slave trade during their hegemony, (ii) that the Dutch seized control of the racialized Atlantic slave trade from the Iberians when they achieved hegemony, (iii) that the British and the French seized control of the racialized Atlantic slave trade from the Dutch as they competed to assume hegemony, and (iv) that Amerikkkaner wealth was largely built on the exploitation of Black slave laborers acquired through the Atlantic slave trade. This is to say, in other words, that all of the capitalist imperialist hegemons to date have made their fortunes, in part, from the racialized Atlantic slave trade. The racialized Atlantic slave trade may be no more but it effectively set the stage and the template for the exploitative extraction of resources from Africa by anti-Black capitalist imperialists. Ay, all of today’s would-be capitalist imperialist hegemons seem more than happy to carry on with the practice of exploiting and extracting resources from Africa, under the auspices of anti-Black logics.

Consider the history of the region known today as the Democratic Republic of Congo, the land that rests upon the craton at the heart of Africa and the land that my maternal ancestors call home.

During the heyday of the Atlantic slave trade, the Long Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, nearly half of the millions disappeared from Africa to the New World as slaves are known to have come from in and around the Congo region, more than from any other region in Africa; millions more died in and around Congo while being marched from the interior to the coast and held in slave prisons, never embarking to the New World; and more millions were never properly enslaved but killed to create the conditions for the slave trade to prosper.

During the Long Nineteenth Century, the concert of European powers that carved up Africa at the Berlin Conference acquiesced to much of the Congo region becoming private property, a giant slave plantation, owned by Belgium’s King Leopold, who oversaw a brutal regime of resource extraction and genocide that killed 10 million people, nearly half of the remaining population of the region.

During the Long Twentieth Century, after Congo gained its independence from Belgium, the Amerikkkaners backed a coup d’etat that resulted in three decades of further impoverishment and degradation, with millions more “murdered by omission,” while the Amerikkkaner-backed dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko oversaw the exploitative extraction of mineral resources from Congo. Subsequently, after Mobutu Sese Seko was deposed, the United Settlers and other capitalist imperialist powers continued to profit from the exploitative extraction of mineral resources from Congo by warlords while more than 6 million more people died in the Congo Wars, the deadliest global conflicts since World War II.

Today, Congo is one of the poorest nations on the planet. More than 30 million people in Congo, approximately a third of the population, are “food insecure,” but Congo also happens to be the source of much of the minerals necessary to build the information technologies that are driving capitalist imperialism’s growth as it pivots from the Euro-Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific.

At each pivotal juncture of the more than five-hundred years of history that I have briefly related here, proceeding right on up to the present day, capitalist imperialists of all stripes and colors have cited anti-Black logics to either justify or overlook their rapacious behavior towards the people of Congo.

Robinson’s focus on the Black Radical Tradition is extremely significant because, given the historical and organic relationships between capitalism, imperialism, anti-Black racism, and the extraction of resources from Africa, it is necessary for every authentically anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist project today to become confluent with the Black Radical Tradition and, vice versa, for the Black Radical Tradition to become confluent with every authentically anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist project. Black lives will matter to anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist projects and, vice versa, the project of making Black lives matter will be an anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist project — that, or neither will be.