Session 4: “Maroon Infrastructures”

Thanks to all who made it to the third session of the AGAPE Seminar & Studio, and to all of the present-absences who shaped the session’s proceedings. It was really great to spend some time (re-)introducing ourselves to one another during this last session. I shall make more time for (re-)introductions during future sessions, and I will be making use of breakout rooms to facilitate this.

We left so many threads of conversation open this past session that I figure we can pick up where we left off and stick with the same background readings for the coming session. That being said, however, I hope to draw upon some case studies and current events in order to create some relays back and forth between abstract ideas and concrete everyday experiences of (im)mobility.

The primer for this upcoming session, printed below, is a critical one. I highly recommend that you give it a read if you didn’t make the last session or if you missed the end of the last session. Just reading the portions in bold will suffice.

Upcoming Session Date: 4 February 2024

Start Time : 10:30 LA / 13:30 NYC / 15:30 São Paulo / 18:30 London / 19:30 Berlin / 21:30 Dar es Salaam / 23:59 Delhi

End Time: 12:30 LA / 15:30 NYC / 17:30 São Paulo / 20:30 London / 21:30 Berlin / 23:30 Dar es Salaam / 02:00 Delhi

Background Readings for the Next Session:

“On Difference Without Separability” by Denise Ferreira da Silva

“A Civil Police?” from Policing Empires by Julian Go

“Bordering Regimes: Four Border Governance Strategies” from Border & Rule by Harsha Walia

The Mexican side of the US-Mexico border wall in Tijuana, Mexico, on March 30, 2019.

Zionist security checkpoint in the occupied West Bank.

Pre-Session Primer:

There were four topics that I endeavored to bring up for discussion during the last session.

First, drawing upon Julian Go’s book Policing Empires, I wanted to discuss the relationship between the policing of racialized peoples in the colonies and the policing of racialized peoples in imperial metropoles, the latter being the boomerang effect of the former. Effectively, what happens in the colonies doesn’t stay in the colonies: the human resources that the metropole extracts from the colony are almost inevitably found to be best controlled by the same means in the metropole as they are in the colonies. Julian Go observes, “The militaristic means and methods that police have imported for home use originate in the frontiers and peripheralized spaces of empire, in effect transforming the “civil” police into not just a militaristic force but a colonial force on home terrain.”

Second, pivoting to Harsha Walia’s Border & Rule, I wanted to make the case that the relationship between the policing of racialized peoples in the colonies and the policing of racialized peoples in imperial metropoles pivots on the policing of the borders between nations in the imperial core and the colonial periphery. Otherwise put, I endeavored to make the case that the administration of bordering regimes is where racialized policing in the colonies and racialized policing in the metropoles become (con-)fused and can no longer be teased apart. The usage of the term “bordering regime” rather than simply the term “border” is important because, as Walia writes, “the border is elastic, and the magical line can exist anywhere. Crossing the border does not end the struggle for undocumented people, because the border is mobile and can be enforced anywhere within the nation-state.” And the internalization of borders within the boundaries of the nation-state is only the half of the matter; the other half is the externalization of the border! Quoting from Walia again, “Border externalization governs through prevention and deterrence far beyond the border itself, such that the definition of the border increasingly refers not to the territorial limit of the state but to the management practices directed at ‘where the migrant is.’”

Border imperialism refers to the manner in which imperial powers, like the European Union and the United States, cite migrants transiting via this post-colony and having their point of origin in that post-colony as an excuse to interfere in the politics and economy of this and that post-colony. Every place that serves as a potential route for “illegal” migration and that harbors large reservoirs of potential migrants is currently in the process of being re-colonized in the name of border security.

Third, I wanted to discuss the problem of statelessness as it relates to all of the above. I endeavored to make the case that there isn’t an exclusive either/or, binary distinction between enstated citizens, on the one hand, and stateless refugees, on the other. The fully enstated citizen of the nation and the stateless refugee are extremes on a continuum: between the two extremes one finds persons who are, to varying degrees, both enstated and stateless.

For instance, a person who lives in a so-called “burdened” or “failed” state is stateless to the degree that they live in a state that is “ungovernable” or “badly governed”. Similarly, racialized “others” within a given nation-state may ostensibly be enstated citizens or permanent legal residents, but they may be considered stateless to the degree that the government of the nation-state discriminates against them because of their race.

Fourth, and finally, I wanted to make the case that a person’s degree of statelessness is, in many if not most respects, determined by their race/racialization. The work of Denise Ferreira da Silva teaches us that the “analytics of raciality” which determine a person’s degree of statelessness are about more than just demography: they are also about geography and historiography. Racialized demographic determinations (white, black, red, brown, yellow) are co-terminous with separable geographic locales (whites from Europe, blacks from Africa, reds from the Americas, brown peoples from South & Southeast Asia, yellow people from East Asia); and also co-terminous with as a sequential historiographic progression (a series of stages of psycho-social-economic “development” that proceed from the Primitive Tribe to the Modern Nation-State, with poor blacks in Africa being associated with the lowliest forms of Primitive Tribalism and rich whites in Europe being associated with the heights of Modern Civilization).

Silva teaches us that the “analytics of raciality” will prevail until we abolish techniques and technologies of government that presuppose and produce demographic determinability (definite & distinct ethnicities and races of people); geographic separability (definite and distinct places where certain people may be said to belong or not to belong); and historiographic sequentiality (definite and distinct stages of psycho-social-economic “development” that all peoples must “progress” through in an ordered sequence). Techniques and technologies of policing and bordering are the most prominent in this regard.

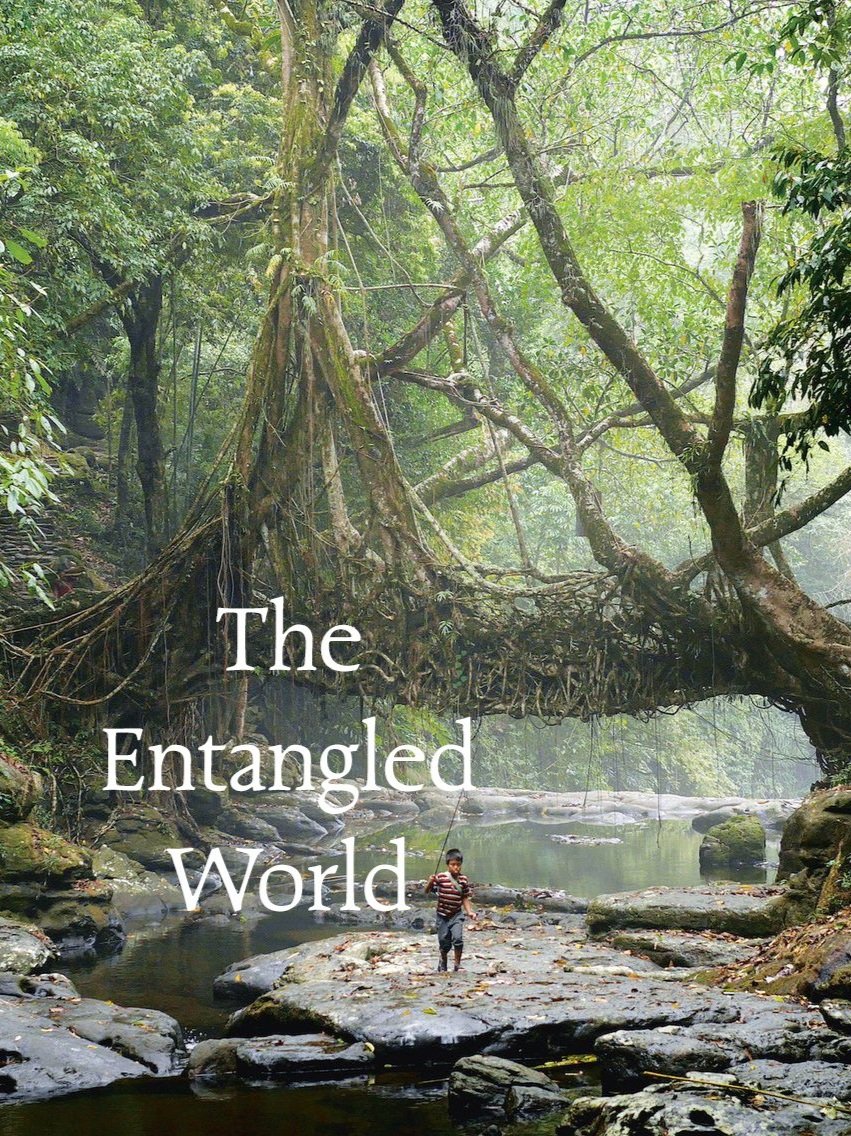

Silva’s work challenges us to deconstruct the “Ordered World” — that is the colonial world, with its determinate demographics, separable geographic locales, and historiographic eventualities; and, in turn, her work encourages us to (re-)construct an “Entangled World” — that is, a convivial world characterized by demographic indeterminacies, geographic non-localities, and historigraphic non-eventualities.

In our next session, I would like to continue to discuss all of the above, but I would like to do so by investigating the “makings of worlds”, generally, and, more specifically, the colonial makings of “The Ordered World” and the convivial makings of “The Entangled World”.

The Makings of Worlds

(Administrative) STATEMENTS

Methods & Measures

For example, consider a recipe that declares the proper methods and proper measures for preparing and serving a meal.

For our purposes, we will consider the administrative statements that declare the proper methods and proper measures for segregating and policing flows of human and non-human resources. How might these colonial statements be deconstructed and how might we (re-)construct convivial statements in the wake of their deconstruction?

(Technical) IMPLEMENTS

Techniques & Technologies

For example, consider the cooking implements for making a meal (pots, pans, stoves, measuring cups, and cooking spoons, etc.), the eating implements for enjoying a meal (plates, bowls, drinking cups, serving and eating spoons, etc.), and techniques for handling such implements.

For our purposes, we will consider the technical implements involved in segregating and policing flows of human and non-human resources and the techniques for handling such implements. How might these colonial implements be deconstructed and how might we (re-)construct convivial implements in the wake of their deconstruction?

(Built) ENVIRONMENTS

Places & Pathways

For example, consider the kitchens where meals are made, the dining areas where meals are enjoyed, and the various pathways into, out-from, and between the two.

For our purposes, we will consider the different places where flows of human and non-human resources are segregated and policed and, in turn, consider the various pathways into, out-from, and between the places. How might these colonial environments be deconstructed and how might we (re-)construct convivial environments in the wake of their deconstruction?

(Dramatic) ELEMENTS

Actors & Factors

For example, consider the dramatis personae who effect the production and consumption of a meal (e.g., cook, server, diner, busser, dishwasher, etc.) and consider the dramatic circumstances that affect the production and consumption of a meal (e.g., season of the year, time of the day, weather at the time, the current political climate, the moods of the cook, of the diners, of the waiters and bussers, etc.)

For our purposes, we will consider the dramatis personae who effect the segregation and policing of flows of human and non-human resources, and consider the dramatic circumstances that affect the segregation and policing of flows of human and non-human resources. How might these colonial elements be deconstructed and how might we (re-)construct convivial statements in the wake of their deconstruction?